The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo est un film américain de genre Documentaire

The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo (2007)

Si vous aimez ce film, faites-le savoir !

Durée 1h16

OrigineEtats-Unis

Genres Documentaire

Themes Afrique post-coloniale, L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité

Note71%

The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo is a 2007 documentary film directed by Lisa F. Jackson concerned with survivors of rape in the regions affected by

ongoing conflicts stemming from the Second Congo War. Central to the film are moving interviews with the survivors themselves, as well as interviews with self-confessed rapist soldiers. The Greatest Silence was nominated for a Grand Jury Prize and won a Special Jury Prize at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival. It was also nominated for two News & Documentary Emmy Awards in 2009. It aired on HBO in January & February 2009.

Synopsis

In 2006, producer/director Lisa F. Jackson travelled alone to the war zones of the Democratic Republic of the Congo documenting the plight of women and girls impacted by the conflicts there. She was "afforded privileged access" to the realities of life in Congo, and found "examples of resiliency, resistance, courage and grace". In a 2008 interview with NPR, Jackson said "I knew going to eastern Congo as a white woman alone in the bush with a video camera that I might as well have landed from a spaceship." Jackson had been a victim of gang rape thirty years earlier, and shared this experience with the survivors she interviewed. Much of the film features these women recounting their stories, which have left them "traumatised and isolated - shunned by society and their families, and suffering life-long health effects, including HIV." Context and background are discussed in interviews with doctors, politicians, peacekeepers, activists and priests. Jackson visits a clinic devoted to treating women with traumatic injury due to sexual violence, particularly cases of vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistula. In addition, Jackson went out into the bush to interview some of the perpetrators, soldiers who spoke without apparent conscience about the women they had raped, and their often bizarre justifications. "You really can say that there's a culture of impunity in the Congo, where none of these men will face arrest for what they've confessed to me on videotape," Jackson noted. The focus of the film, though, is the stories of the victims, "who just poured their hearts out to me with these stories, including over and over again, please take these stories to someone who will make a difference.Commentaires

Postez un commentaire :

Suggestions de films similaires à The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo

Il y a 8965 ayant les mêmes genres cinématographiques, 5386 films qui ont les mêmes thèmes (dont 8 films qui ont les mêmes 6 thèmes que The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo), pour avoir au final 70 suggestions de films similaires.Si vous avez aimé The Greatest Silence: Rape in the Congo, vous aimerez sûrement les films similaires suivants :

Darfur Now (2007)

, 1h38Réalisé par Ted Braun

Origine Etats-Unis

Genres Documentaire, Policier

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

Acteurs Don Cheadle, George Clooney, Arnold Schwarzenegger

Note66%

Les Enfants de l'Exil (2007)

, 1h26Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'enfance, L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité

Acteurs Nicole Kidman

Note78%

Quatre jeunes garçons originaires du Soudan embarquent pour un voyage aux États-Unis après des années de dérive en Afrique sub-saharienne à la recherche de sécurité.

, 52minutes

, 52minutesOrigine Algerie

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

En 1939, la fin de la guerre civile espagnole oblige des milliers d’hommes, de femmes et d’enfants à fuir l’Espagne franquiste. En Algérie, l’administration française ouvre des camps pour les accueillir. 70 après, un jeune Algérien enquête sur ces camps. Malgré l’absence d’archives, les traces ont survécu à l’oubli collectif et transparaissent dans l’Algérie d’aujourd’hui.

Lost Boys of Sudan (2003)

, 1h27Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'enfance, L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité

Note74%

المنام (1987)

, 45minutesRéalisé par Mohamed Malas

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'immigration, Religion, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la religion, Politique, Religion juive

Note62%

The film was composed of several interviews with different Palestinian refugees including children, women, old people, and militants from the refugee camps in Lebanon. In the interviews Malas questions his subjects about their dreams at night. Through their answers, the film attempts to reveal the underlying subconsciousness of the Palestinian refugee. The dreams always converge on Palestine; a woman recounts her dreams about winning the war; a fedai of bombardment and martyrdom; and one man tells of a dream where he meets and is ignored by Gulf emirs. According to Rebecca Porteous, the film constructs "the psychology of dispossession; the daily reality behind those slogans of nationhood, freedom, land and resistance, for people who have lost all of these things, except their recourse to the last.

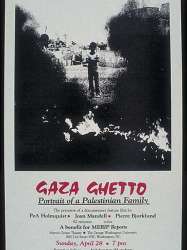

Gaza Ghetto (1984)

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, La famille, L'immigration, Religion, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Documentaire sur la religion, Politique, Religion juive

Note56%

The Forgotten Refugees (2005)

, 49minutesGenres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'immigration, Religion, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la religion, Politique, Religion juive

La Famille de Nicky (2011)

, 1h36Réalisé par Matej Mináč

Genres Drame, Documentaire

Thèmes L'immigration, Le racisme, Religion, Documentaire sur la discrimination, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la religion, Politique, Religion juive, Documentaire sur la Seconde Guerre mondiale

Acteurs Klara Issova

Note80%

"La famille de Nicky" est l'histoire extraordinaire de Nicholas Winton, surnommé le Schnindler britannique, qui avant le début de la seconde guerre mondiale, entre mars et août 1939, a sauvé 669 enfants tchèques et slovaques, pour la plupart juifs, du génocide nazi. Le film mêle fiction, documents d'archives inédits, et témoignages émouvants des protagonistes de cette histoire, parmi lesquels Nicholas Winton en personne et Joe Schlesinger, journaliste à la CBC et narrateur du film. La "famille" de Nicholas Winton compte aujourd'hui plus de 5 000 personnes dans le monde entier, qui lui doivent la vie.

Zramim Ktu'im (2010)

, 1h15Origine Israel

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, L'environnement, Religion, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur l'environnement, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Documentaire sur la religion, Politique, Religion juive

Paths of lives are crossed in one village in the West Bank. Along the broken water pipelines, villagers walk on their courses towards an indefinite future. Israel that controls the water, supplies only a small amount of water, and when the water streams are not certain nothing can evolve. The control over the water pressure not only dominates every aspect of life but also dominates the spirit. Bil-in, without spring water, is one of the first villages of the West Bank where a modern water infrastructure was set up. Many villagers took it as a sign of progress, others as a source of bitterness. The pipe-water was used to influence the people so they would co-operate with Israel’s intelligence. The rip tore down the village. Returning to the ancient technique of collecting rainwater-using pits could be the villagers’ way to express independence but the relations between people will doubtfully be healed.

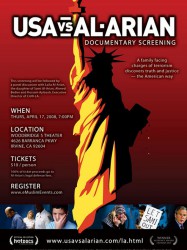

USA vs. Al-Arian (2007)

, 1h42Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, Religion, Le terrorisme, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Documentaire sur la religion, Documentaire sur le terrorisme, Politique, Religion juive

Note70%

Connexion

Connexion