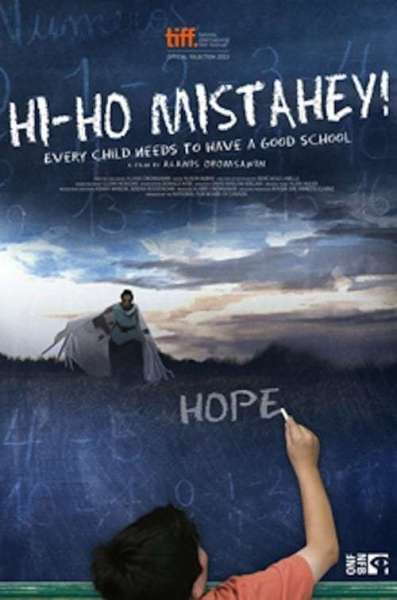

Hi-Ho Mistahey! est un film canadien de genre Documentaire

Hi-Ho Mistahey! (2013)

Si vous aimez ce film, faites-le savoir !

- Infos

- Casting

- Infos techniques

- Photos

- Vidéos

- Passages TV

- Citations

- Personnages

- Musique

- Récompenses

Hi-Ho Mistahey! is a 2013 National Film Board of Canada feature documentary film by Alanis Obomsawin that profiles Shannen's Dream, an activist campaign first launched by Shannen Koostachin, a Cree teenager from Attawapiskat, to lobby for improved educational opportunities for First Nations youth.

The film premiered on 7 September 2013 at the 2013 Toronto International Film Festival. It was subsequently named first runner-up for the festival's People's Choice Award in the documentary category, behind Jehane Noujaim's The Square.

The film's title is Cree for "I love you forever." Obomsawin has said she heard about Koostachin's story from children's rights activist Cindy Blackstock. Obomsawin had been in the community of Attawapiskat working on this film when the Attawapiskat housing and infrastructure crisis broke. So she put this project aside and completed her film The People of the Kattawapiskak River, before completing Hi-Ho Mistahey!

The film was a shortlisted nominee for the Canadian Screen Award for Best Feature Length Documentary at the 2nd Canadian Screen Awards.

^ "TIFF 13: Alanis Obomsawin on Hi-Ho Mistahey!". Playback, 13 September 2013.

^ "TIFF 2013: 12 Years a Slave wins film fest’s top prize". Toronto Star, 15 September 2013.

^ "Attawapiskat woman's struggle focus of TIFF film". CBC News. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

^ Adams, James (1 November 2013). "Hi-Ho Mistahey!: Earnest doc on native education has heart in the right place". Globe and Mail. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

^ "Canadian Screen Awards: Orphan Black, Less Than Kind, Enemy nominated". CBC News, 13 January 2014.

Commentaires

Postez un commentaire :

Suggestions de films similaires à Hi-Ho Mistahey!

Il y a 8958 ayant les mêmes genres cinématographiques, 3749 films qui ont les mêmes thèmes (dont 5 films qui ont les mêmes 3 thèmes que Hi-Ho Mistahey!), pour avoir au final 70 suggestions de films similaires.Si vous avez aimé Hi-Ho Mistahey!, vous aimerez sûrement les films similaires suivants :

Estudiar en primavera (2014)

, 53minutesGenres Documentaire

Thèmes Le thème de l'éducation, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

Note83%

Prisoners of a White God (2007)

, 51minutesGenres Documentaire

Thèmes Le thème de l'éducation, L'enfance, Esclavagisme, Religion, Sexualité, Erotique, Prostitution, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Documentaire sur la prostitution, Documentaire sur la religion, Documentaire sur la maltraitance des enfants, Politique, Maltraitance des enfants

A City Decides (1956)

, 27minutesRéalisé par Charles Guggenheim

Origine Etats-Unis

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Le thème de l'éducation, Le racisme, Documentaire sur la discrimination, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

Note64%

Il m'a appelée Malala (2015)

, 1h28Réalisé par Davis Guggenheim

Origine Royaume-uni

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Le thème de l'éducation, L'enfance, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la maltraitance des enfants, Films pour enfants, Maltraitance des enfants

Note69%

Trois ans après l'attaque qui l'a laissée en partie sourde et paralysée d'une partie du visage, Malala Yousafzai raconte sa nouvelle vie en Angleterre, à Birmingham où sa famille est réfugiée depuis son attaque. On la suit dans la vie de tous les jours, dont celui où, pour son seizième anniversaire, elle prononce un discours devant l'Organisation des Nations unies. Davis Giggenheim a suivi son quotidien pendant dix-huit mois.

War Zone (1998)

Réalisé par Maggie Hadleigh-West

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité

Acteurs Maggie Hadleigh-West

Note64%

Twist of Faith (2005)

, 1h27Réalisé par Kirby Dick

Origine Etats-Unis

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes L'enfance, Religion, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la religion, Documentaire sur la maltraitance des enfants, Maltraitance des enfants

Acteurs Jeff Anderson

Note71%

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes L'immigration, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité

Note71%

Pas ma vie (2011)

, 1h23Réalisé par Richard Young

Origine Etats-Unis

Genres Documentaire, Policier

Thèmes L'enfance, Esclavagisme, Maladie, Sexualité, Erotique, La pédophilie, Prostitution, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la prostitution, Documentaire sur la santé, Documentaire sur la maltraitance des enfants, Folie, Le handicap, Maltraitance des enfants

Acteurs Glenn Close

Note77%

Ce film dépeint les pratiques cruelles et déshumanisantes de la traite des êtres humains et de l'esclavage moderne à l'échelle mondiale. Filmé sur cinq continents, dans une douzaine de pays, "Not My Life" emmène le spectateur dans un monde où des millions d'enfants sont exploités via un panel stupéfiant de pratiques, incluant le travail forcé, le tourisme sexuel, l'exploitation sexuelle, et les enfants soldats.

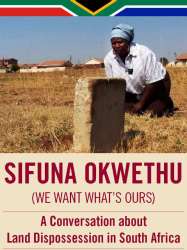

Sifuna Okwethu (2011)

Origine Etats-Unis

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, Le racisme, Documentaire sur la discrimination, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

The film tells the story of both sides claiming the same land as their own. The Ndolilas family’s land was taken by the apartheid government in the 1970s without compensation, and ever since then they have been on a quest to get it back. Standing in their way are working class black homeowners who purchased portions of the Ndolila's land during apartheid. For the homeowners, the land and houses they have legally purchased are a reward for their hard work and the fulfillment of their hopes and dreams for a better life in the new democracy. For the Ndolilas, the land is part of their family legacy and hence deeply intertwined with their identity. Both sides have a legitimate right to the land, and the film encourages viewers to think about whose rights should prevail.

, 1h31

, 1h31Réalisé par Peter Raymont

Origine Canada

Genres Documentaire

Thèmes Afrique post-coloniale, Le racisme, Documentaire sur la discrimination, Documentaire sur le droit, Documentaire sur la guerre, Documentaire historique, Documentaire sur une personnalité, Documentaire sur la politique, Politique

Note80%

Documentaire sur l'histoire du Lieutenant General canadien Roméo Dallaire, dont la manière de diriger la mission des Nations Unies durant le génocide au Rwanda en 1994 a été très critiquée.

Connexion

Connexion